It wasn’t until he met his uncle at Mexico City’s bustling airport in April that Amador Alcantara realized they shared the same destination: a sprawling Norfolk County farm called .

Alcantara was happy. He’d spent almost 20 years travelling back and forth to Canada as a migrant worker. This year, he’d have family by his side.

But in the months that followed, 200 of Alcantara’s co-workers would test positive for . His uncle, , 55, would not survive the massive outbreak — one of the largest in the entire province.

In an interview with the Star, the first since his uncle died in June, Alcantara described Chaparro as a respectful and friendly man whose death has overwhelmed his family.

“We shared a lot of moments together while we were working,” said Alcantara. “The situation is very sad and painful.”

On Tuesday, Alcantara also testified about his experiences with Scotlynn’s outbreak before the Ontario Labour Relations Board.

It forms part of a reprisal complaint filed last month by , who was Alcantara’s bunkmate. The claim alleges Flores was fired and threatened with deportation by Scotlynn after raising concerns about safety issues at the farm.

Scotlynn has denied the allegations — and in a hearing last month, the farm’s founder Robert Biddle said he could not have fired Flores because he was sailing to a “small island” on the date in question.

In testimony Tuesday, Alcantara said he was present when Flores was terminated.

“The boss said (to Flores), “I don’t want anyone who is causing conflict on this farm, you have to go back to Mexico,’” said Alcantara.

The reprisal complaint brings into focus migrant workers’ ability to effectively assert their rights amidst a pandemic that has led to an estimated 1,300 farm labourers testing positive for COVID-19 in Ontario alone.

“This case is emblematic of the deep structural problems in the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program and the system of temporary migration in Canada,” said Karen Cocq of Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC).

Lack of permanent immigration status “effectively condemns” migrant workers to abuse because employers can send them back to their home countries for almost any reason, she added.

Separately on Tuesday, the provincial and federal governments jointly announced $26.6 million in funding for agricultural employers to improve health and safety on farms. Under the program, farmers can claim up to $15,000 for “preventative expenses” including workplace modifications, protective gear, and transportation. They can also apply for up to $100,000 to complete housing modifications and other larger investments in safety.

“Protecting the health and well-being of all farm workers who are helping ensure the food security for Canadians has been a top priority since the beginning of the pandemic,” said Marie-Claude Bibeau, federal Minister of Agriculture.

“This isn’t the kind of measure that responds fundamentally to the core problems built into the program,” said Cocq.

In his interview with the Star, Alcantara said his uncle was asked by the Mexican authorities to go to Scotlynn this year because high turnover at the farm was making it difficult to fulfil the required number of workers. The Star has previously on the history of complaints filed by migrant workers at Scotlynn, including long-standing reports of bedbug infestations, overcrowding, and unsafe working conditions.

Housing was amongst Alcantara’s concerns when he arrived in Canada in April, he told the labour board Tuesday.

“There wasn’t space to distance,” he said through a translator. “It was very close quarters.”

, who runs Scotlynn and is the son of founder Robert Biddle, has previously said he spent over $700,000 on quarantine measures and provides “climate-controlled” housing with lounge areas and soccer fields for leisure time.

After their mandatory two weeks quarantine in a hotel, Alcantara told the Star he and his uncle were placed in different apartments of the same housing complex. The bunkhouse was known colloquially as los quemados — the burned — after a small fire caused years ago by a worker who left a pot too long on the stove.

A few weeks into the season, Alcantara told the Star he noticed his uncle looking ill. Initially, Alcantara put it down to cold weather and lack of warm clothes. But soon, workers sharing an apartment with Chaparro said his condition had worsened.

On June 20, after several weeks battling the virus including hospitalization and intubation, Chaparro died. Scotlynn informed workers that night. Alcantara told the labour board he watched Flores tell supervisors they “should have done more for that man who died.”

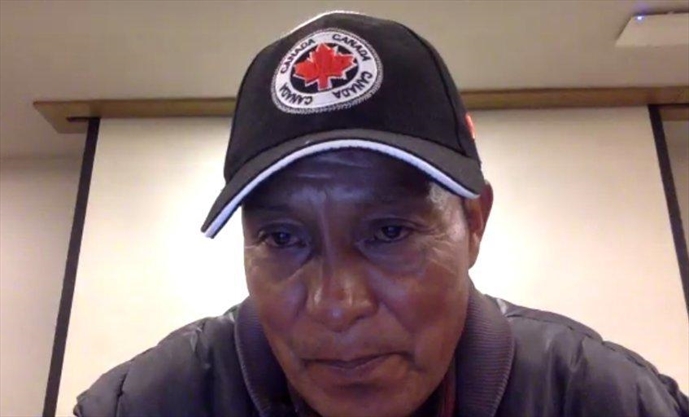

“(The supervisor) said, ‘Who are you to say this to me? He’s not even one of your relatives. Why are you complaining?’” said Alcantara, who testified over Zoom from Mexico City in a maple leaf-emblazoned baseball cap.

The next day Flores was terminated, according to submissions made on his behalf by Parkdale Community Legal Services (PCLS). Flores subsequently took refuge in a safe house, the PCLS submissions said.

In closing arguments Tuesday, Scotlynn lawyer Paul Hosack said there was “simply no evidence” to support the claim’s allegations.

Hosack said Flores had spoken up about “something that happened in the past” and that the farm had reached out to Flores after he fled to tell him he could return to work.

“Our position is the claim should be dismissed,” said Hosack.

PCLS lawyer John No said the return-to-work offer was only made after Flores filed his complaint at the board. Noting that employers carry the burden of proof in reprisal cases, No said no evidence had been presented to provide an alternative explanation for Flores’s termination.

Flores is seeking $40,400 in lost future earnings and damages. He also hopes to see broader change to protect workers, he told the board Tuesday.

“I am just a farm worker tired of what is happening to us,” he said. “We have to leave our homes and families and cultures at home in Mexico to serve here in Canada and I think permanent residency is the least we are owed.”

With hearings concluded, labour board alternate chair Matthew Wilson will issue a written decision on the reprisal case in the coming months.

For Alcantara, who has now returned to Mexico, being back in the hometown he shared with his uncle is a source of comfort. But for Chaparro’s wife and four children, the grief is still paralyzing.

“It has taken a toll on them as a family,” Alcantara said. “But they feel there’s nothing they can do.”

Sara Mojtehedzadeh is a Toronto-based reporter covering work and wealth for the Star. Follow her on Twitter: